The final book, St. Louis Parks, turned out well, and it is well-recieved by the public. Please click here if you would like to purchase a copy, autographed by me.

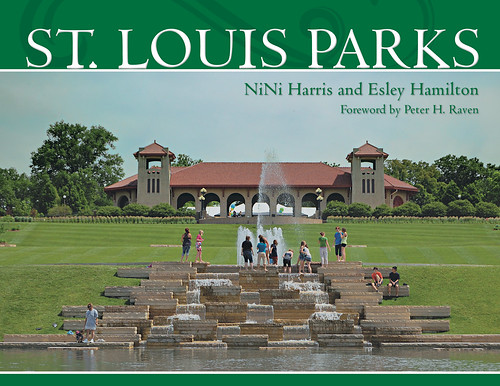

My publisher selected the photo above for the cover of the book, and I generally like it. It isn’t perfect — the sky appears to have a slight greenish tone, especially when seen under fluorescent illumination (although it is correctly white-balanced, and I didn’t alter the hue in post-processing), and the image is a bit darker than I’d like. The formal symmetry, with the fountain and building centered with each other and with the frame, is pleasing to me, but it is slightly off — although this is offset by the presence of the spine, not seen here, on the left hand of the book. What makes the photo, I think, is the presence of teenagers enjoying the fountain; having human subjects in a landscape photo is often appealing. The photo is technically OK, has a good subject, and is composed adequately, making it, in the opinion of my publisher, good enough to be on the cover of a book.

Generally speaking, there is a certain lightness of spirit or relief you can get when you leave certain decisions to others — were I to have selected the photos for the book, I think I would have agonized too much over them, seeing little else than flaws. Instead, my publisher selected images that he thought had general appeal, and he usually selected my favorites. Artists are often not the best judges of their works. Getting a sense of what is good takes understanding, time, and experience, as well as receiving the good judgement of others.

The first step towards getting better in photography, or any art, I think, is to understand why your works are disappointing, and understanding what makes good images superior. This can be exceptionally difficult, for oftentimes it is hard to put vague feelings into words. Determining what actions to take can be difficult also, for it requires an understanding of the technology. For example, you may find that your photographs are too yellow, but you have to understand color theory in order to know that you must make the photos more blue to cancel out the yellow, and you have to understand manual white balance on the camera, or the use of post-processing on the computer to correct for this flaw.

A Lofty Target

It is easy to become inspired by awesome works of art, which can give you the desire to be able to do the same. When I started work on this project, I examined many highly-regarded landscape photos — and landscape paintings — and sought out good advice. What do the best landscape photographers do? How can I do the same?

Click here for some highly-rated images. Do you find those images good? If so, what in your opinion makes them good? If you don’t like them, what landscape photos do you find appealing? Why?

This kind of inspiration is a pull from above, and so serves as a worthy goal. But it can be simultaneously fruitless and discouraging if you don’t have the right attitude. If your target is so lofty, and you never come even close to hitting the target, do you want to give up?

Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River (1942) Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Park Service. (79-AAG-1) [source]

I see two problems.

One is the desire to “fill Ansel Adams’ tripod holes.” This desire to duplicate that one Great Photograph is often present with ardent photographers who are more than beginners, who may be somewhat knowledgeable, but who may take a dilettantish view of the subject. While perhaps this is a worthy exercise for some, it leads to a repetition of photographs of the same subject from the same location, and so can turn an awesome subject into something dull or overly familiar. Typical landscape subjects, duplicated extensively, include Adams’ Half Dome, and photos of Delicate Arch and Mount Fuji, and we can include numerous other tourist attractions, such as the Gateway Arch.

But this trivializes the effort of the original photographer; Adams’ image of Half Dome is much more than simply location and subject, for time of day and year, and the weather were important, as well as his extensive darkroom work.

This attitude also leaves out room for improvement. Perhaps Adams was tired, and placed his tripod simply because his feet hurt, it was getting late in the day, and he didn’t want to walk any further. Perhaps there is a much better location which will never be discovered because of Adams’ precedent. We also have new technology, barely dreamed of in those days. What are the possibilities today?

But you should ask yourself: why spend the money, time, and trouble to travel to Yosemite Valley? Aren’t there worthy subjects close to home? If you are being paid to travel to remote locales, then certainly you can explore the world photographically. But in general, if you want to be a good landscape photographer, you have to take lots of photos of landscapes, and you can’t expect to pack all of your experience into a two-week vacation. Are there undiscovered landscapes near your home, ones that are destined to be featured in a future Great Photograph? Perhaps you can photograph what you know and love — perhaps, by being a local, you can see some detail that all the tourists miss. Never forget that what is commonplace to you is exotic and unusual to most of humanity.

I live not too far from Forest 44 Conservation Area, which is near Valley Park, Missouri; I’ve long thought that some good landscape photography can be had here, and am willing to keep trying to get the good shot.

I used the example of Ansel Adams (1902-1984) here simply because he is the only photographer that most people know by name, and because beginners will often say that they are inspired by his work. But there are many other great photographs and great photographers (and let’s not forget about painting) — perhaps we ought to do research and broaden our horizons in finding inspiration. Click here for a list of notable photographers. Click here to find notable painters.

Another problem is similar: people want to use the same gear used by the Great Photographer. “Did Adams shoot Canon or Nikon?” people actually ask. Clearly this can become a great expense, and can be fruitless and counterproductive if you don’t know how to use your gear for best effect. I mainly shot St. Louis Parks with what is now a rather antiquated digital camera with ordinary optics, and I’ve already completed the principal photography for my next two books with the same equipment: “But,” I say to myself, “my next projects will be taken with a Nikon D800E. I also need to upgrade my lenses.” Yes, an upgrade would be very nice, but my results are certainly adequate for my present needs. Maybe I’m pushing the limit of optical quality (especially on two-page spreads), and maybe a D5100 (much cheaper than the D800E) is more in line with what I really need. But chasing gear — even by a professional — can turn photography into an expensive collectors’ hobby, and perhaps the money can be more wisely spent.

This photo from the book gets lots of positive comments. I took it with a cheap point-and-shoot camera that you can buy used for about $200. These trees would have made an ordinary snapshot if not for the late afternoon light.

There are a few things that I’ve learned from studying highly-regarded landscapes, both paintings and photos, and nearly all the best landscapes have these things in common:

- A good landscape is either of an epic subject, or it is of a beautiful subject, or both.

- Ordinary landscapes can be good if there is significant use of unusual camera work, such as good use of a wide angle lens, effective supplemental lighting, an unusual camera position, or other uncommon things of interest.

- Good landscapes are taken around sunset or sunrise, and sometimes at night, and almost never during midday.

- Good landscapes often depict unusual weather, such fog or snow, or impressive clouds, or dramatic lighting.

- Monochrome landscapes typically have a full range of tonalities; color landscapes typically have distinctive color, at least in detail.

- A good landscapes has an essential unity, a clear subject, and the composition harmonizes well with the subject, enhancing and directing attention towards it. Good landscapes are considerably more abstract than ordinary snapshots.

- Including a human in the image can transform the meaning and impression of the image dramatically, often for the better.

- Good landscapes are almost always made with good equipment and good technique. Rarely do you see a good landscape with obvious technical mistakes or bad image quality, as you will often see with excellent photojournalistic images.

As I mentioned, while a lofty target can be a great inspiration, you have to examine yourself and understand your limits and your capabilities. If you are 5 foot tall or 55 years old, a dream of becoming a professional basketball player is unrealistic; it is even unrealistic for the vast majority of prime, top-rated young athletes. Don’t have extraordinary expectations unless you have a reason for your hope. Perhaps there is something else you can do well? What are your talents?

Please see the article A Good Photograph for additional lofty meditations.

Flee from Evil

As I mentioned, finding inspiration in the best work done by the masters is important, but can be discouraging, since the target is so high. Another, perhaps easier, approach is to identify errors or problems in your photos, and then learn how to eliminate them. Avoiding bad photography is a push from below, and has the advantage of being easy to learn. Some dislike this negative approach, full of “thou shalt nots,” but it helps if we both can identify the good and how to avoid evil.

It was not my intention to set the focus on the branches seen here on the right, but that is what my camera’s automatic focus selected. That camera was nearly impossible to manually focus. My current camera (and many DSLRs) aren’t too good for manual focus, which is a shame.

Taking this bottom-up approach means that you first have to understand your gear and the basic principles of photography — dull things, perhaps, far removed from what many people call Art — but you can’t take a photograph unless you have a camera, and you usually can’t take a good photograph unless you know how to use your camera.

However, I recommend that a beginner take a multi-pronged approach to photographic technique, working on improving in parallel the choice of subject, camera settings, composition, and general appeal.

This is a particularly bad photo, taken under dull skies, with a huge pile of dirt on the right, a number of barely visible barges, and lots of dark muddy detail in the middle. What is the subject of this photo? What did I want to depict? If I wanted to depict a pile of dirt, why did I not depict it boldly and purposefully? Or why didn’t I zoom in to the barges? Or, rather, should I leave my camera home when the skies are overcast and uninteresting? Also, I might add that digital cameras often render shadows poorly, as seen here, making post processing or supplemental lighting almost a requirement for good photography.

My publisher considered using this photo. While the stray grasses at center bottom are distracting, and the trees are in the way, this photo still has a good subject with human interest. I specifically zoomed in to get one major subject, the boat, and the two onlookers on the left and right, without huge expanses of uninteresting detail. Not great, but it is an improvement over the previous photo.

Far more interesting (despite the tree branches) is the following photograph of tugboats, also on the Mississippi River:

But since this photo was not taken from one of my assigned parks, it could not go into the book.

Here are some mistakes that you ought to avoid:

- Bad focus. Be sure you focus on your subject. Automatic focus will often select the closest object, which will often make a distant object blurry. For landscapes, you can hardly go wrong if you focus on the most distant significant detail and use a good aperture. Be aware that the larger the sensor on your camera, the larger the chance that you will have bad focus because of narrowed depth of field.

- No clear subject. What, specifically, is important in your photo? What catches your attention in the scene? What is distracting? Are you sure that your photograph will capture the scene in a way that will show the interesting subject clearly?

- Using a wide angle lens to ‘get the whole scene.’ Is the whole scene interesting? Be aware that a wide angle lens will make distant detail look smaller, while emphasizing the foreground: is this what you want? Ultra wide angle lenses will distort the edges; do you intend that?

- Bad framing. How much sky is in your photo? Is the sky interesting? Does too much space surround your subject? Will getting closer, or using a telephoto lens help? Is your subject nicely placed within the frame? Does your camera position and framing harmonize with the symmetry of the subject?

- Clutter. Tree trunks and branches, randomly scattered across your image, can detract from your photo of a forest. Rather, seek out scenes that are simpler, cleaner, more ordered, and more uniform. A certain amount of abstraction will often make a better image.

- Softness. Landscapes are usually enhanced with crisp detail. Softness due to poor optics or technique is often disappointing.

- Bad exposure. Is significant detail lost because of over or underexposure? Be aware that having even one of the three color channels overexposed will cause a shift in color. See the article Three Opportunities for Overexposure for details. Better lighting, high dynamic range techniques, or significant post-processing on the computer may be needed to correct for this.

- A tilted camera. Do you intend the horizon line to be crooked? With wide angle lenses, be aware that there may be a significant perspective distortion on vertical lines if the camera is not held level.

- Bad white balance. Most cameras do a good job when taking photos in broad daylight, but photos in the shade may turn out blue, or photos at sunset may have a disappointing lack of golden color. Be aware of the limits of automatic white balance, and override the function manually to get the right color. See the article White Balance, Part 1 for more details.

- Bad color. Are the colors captured by the camera dull and lifeless? If so, would your image look good in monochrome? Either post-processing, choosing a better time of day, or a more interesting weather condition may help.

- Bad lighting. Do shadows enhance your subject, or do they distract from it? Does the soft uniform lighting from an overcast sky improve your image, or does the white featureless sky distract from it? Does dappled sunlight enhance your image, or does it make the scene unintelligible?

- Shooting into the sun. Do you intend to have lens flare and other optical artifacts in your image? Do you intend to have a black, featureless foreground, or an overexposed sky?

- Not knowing your limitations. Most cameras at this time do not have good low-light performance: taking a photograph at dusk, without a tripod, may give you photos that have excessive noise or blur due to camera shake. Does your knowledge of theory outstrip your experience, leading to misguided photographic choices? Is your theoretical knowledge weak, leading you to have a borderline superstitious understanding of your camera? Are you seeking outside help to improve your photography? Do you shoot with a friend or with a group? Do you seek critique of your photos?

- Chasing gear. Do you think that better camera gear will automatically get you better photos without any effort on your part? Is there a better use for your money? Squeezing the last bit of quality from inferior camera equipment can be an excellent experience, and not just a frustration.

- Laziness. Do you intend to take superior photographs, but aren’t willing to make an extra effort to get them? Are you willing to get up earlier than is customary for you? Are you willing to wait until the lighting is better? Are you willing to be somewhat uncomfortable when finding a better place to take a photograph?

- Not knowing your audience. Are you shooting for a family album, for a popular book, or for a curated art gallery? Your images may vary depending on your audience expectations.

Keeping these mistakes in mind can help you become a better photographer. But many of these things can be a good choice if you know that it will make for a superior photograph. Ultimately, it is the wisdom that comes from knowledge, experience, and inspiration that will help.

Some Examples

I was provided with a list of parks to photograph. Sometimes, an assigned park would be only a rectangle of grass, perhaps surround by a fence. How can I take an appealing photograph of that? But I had a job to do. Driving around this park, I saw something in this row of bushes, it caught my eye, although this photo was disappointing.

My camera’s automatic white balance feature subtracted out the color of the sun, low in the sky. Like photos taken by most digital cameras, both highlight and shadow detail are flattened and dull. This required more than good camera work, instead, I had to bring out this detail in post processing.

Here the color of the sky is restored, and we can see texture there, as well as in the snow with its distinct animal tracks. We can even see some texture in the dark bushes, and the chain link mesh of the fence is more distinct. With cropping, we have a composed row of four bushes that harmonize with the fence. I knew that there was an interesting photo to be found here.

Saint Louis gets snow frequently in winter, but it typically does not get deep and it melts quickly. One night, snowfall was heavy and I stayed out until 4 in the morning taking photos to document the unusual weather. The light in the city was an orange color due to street lighting reflecting off the large falling flakes, and it was so bright that I was able to hand-hold the camera easily. I liked this bridge, and even took nine photos of it from this position, but the photos are slightly disappointing. A different camera position improves the subject:

Railroad tracks — and footprints — lead into the distance, while the bridge acts as a frame for another bridge. While many Saint Louisians are familiar with this park, undoubtably some have seen this bridge from this angle, but not under these weather conditions. A possibly ordinary subject becomes interesting.

A number of photos from that night made it into the book, because the color was so strong and the weather and time of day so unusual. That night made common things uncommon.

Generally speaking, the best landscape photographers are willing to get wet, muddy, and hike the extra mile in order to get their shot, which is something that I try to remind myself when I’d rather be at home in the air-conditioning, sitting in front of my computer.

Taking numerous shots of the same subject, and examining their strengths and flaws, can improve your photography:

Here we have the same scene as found on the book cover. I’ve taken many photos of it over time, and another view of this taken at night found its way into the book. Here I attempted to align the fountain precisely with building in the background, but I didn’t bother to keep the camera horizontal. The image is underexposed, even though that particular camera has little dynamic range to spare.

Note that I took it with a wide angle lens. Many beginning landscape photographers think that they need a wide, or ultra wide angle lens, in order to ‘get the whole scene in,’ and undoubtedly I thought that I needed to set the zoom to wide for the same reason. But look at how much of the image is featureless! The sky and the water here add nothing to the photo, it is inessential detail, as is much of the green grass. For this reason, it is commonly advised that you ought to ‘fill the frame’ with your subject — get close with either your zoom or your feet. (I might add that you probably ought to leave a little room around your subject for cropping.)

Please compare the relative sizes of the building and waterfall in both images. The cover photo was taken from a greater distance with a telephoto lens, and so the building and waterfall appear to be closer together; because the angle of view of the lens is smaller, we have less inessential detail of the sky, grass, and water. In the cover photo, the narrow strip of water serves to frame the main subject and act as a transition to the edge of the cover, while the relatively featureless sky is not wasted space, for in it we find the names of the authors.

Finally, notice that the two figures on the right are walking away from the fountain, and contrast that with the youth on the book cover, who appear to be enjoying the fountain. The eye is drawn towards humans, and if the humans in the photo appear to be uninterested in the scene, what does that tell you about your subject? I’ve seen some excellent landscapes where we are shown a human figure, looking at the scene with the same awe that the photographer or painter would want us to feel.

I had taken many photos of that waterfall over a period of time, and many of those photos were taken with considerable care and scene analysis. But on the day I was taking the cover photo, which was a Thursday, I undoubtably was busy doing other things, and I wasn’t out taking photos, but I did have my camera with me. As I approached the waterfall, I noticed the youth at play, and thinking that this was interesting, I took three photos as I was getting close. I knew I would have the right shot when I was centered on the waterfall: I took that final photo and then left. Within less than three minutes, without much forethought, with little setup, with just one photo, and under non-optimal conditions, I got the prime shot. I knew that it would be good. Experience helps.

Here is a particularly bad example:

These old ruins are an interesting subject, but this photo is typically of innumerable bad landscape photos. What does my photo show? Clearly, there are the remains of some sort of structure here, but the vegetation and especially the dappled lighting makes this a confusing and unsatisfactory image.

I usually find overcast days poor for landscapes, but the diffuse sky lighting might be a benefit here. Zooming in towards the door to the cave might also help isolate an interesting subject. Also, lack of vegetation in the wintertime might benefit by decluttering the scene.

I’m mainly an architectural photographer, and I usually find people in my photos to be a distraction from the purity of the form of the building. But armed with this attitude, the results of my first day of shooting were dismal:

This was taken near sunset, and the park was illumined by huge clouds in the sky, reflecting orange light from the setting sun. More photos from that evening can be seen here. I like those photos for several reasons, including the color of the light, the attractiveness of the park architecture, and the presence of people, waterfowl, and flowers. I also used camera work, I think, to good advantage — I shot these with a telephoto lens at wide aperture, and fixed the camera white balance to Daylight so as to retain the color of the lighting. This particular photo has a number of flaws, and I think the tree in the middle foreground is unfortunate, although the scene is still somewhat interesting.

It’s far too easy to take a dull photo:

Dull, dull, dull. Being bored is not only a waste of time, it can also be dangerous.

Dull photographs are often weak in texture and color. For this reason, many photographers tend to oversaturate their photographs, boosting the color beyond what is reasonable. I have mixed thoughts about this practice; for sure, digital images lack the contrast, texture, and color range found in real life, and so increased saturation is a legitimate technique to counteract the limits of the medium. Art purchasers also seem to prefer some level of increased saturation. On the other hand, this can harm texture as the medium is driven to the edge of its color gamut, and turn an otherwise plausible landscape into something that looks fake, or some would say dishonest.

Alternatively, you can select subjects that are inherently colorful:

The blue water here caught my eye. But a white sandy beach, in the Saint Louis area? I never thought there would be such a thing nearby. Interesting, unique landscapes are not necessarily far from home. According to Flickr, there are currently only about 100 photos taken at this park, and so it is barely discovered photographically.

The color of light, rather than merely the color of a subject can make an image appealing, and for this reason, many photographers avoid mid-day. Sunrise and sunset give a natural warm glow to an image, while dusk and dawn give a cool color. Please recall that highly-rated landscape photos are largely taken during these times of day. I am not saying that you can’t take an awesome shot at midday, I’m just saying that most excellent landscape photographs are not taken during that time of day.

Automatic white balance in a digital camera attempts to subtract out the color of light, with the goal of leaving neutrally-colored subjects in real life appearing to be neutral in the captured image. For example, a white piece of paper typically reflects light of all frequencies uniformly, and in a white balanced image, the red, green, and blue channels recording the white paper will all have the same value, which shows us that the color of the light was eliminated.

But sometimes we don’t want to subtract out the color of light. Many photographers, including me, will set the camera to a fixed ‘Daylight’ white balance when shooting at sunrise and sunset. This keeps a good balance between the orange color of the waning sun, and the deep blue of the sky, without neutralizing either color, and so makes the final image particularly colorful.

Besides the color shown here, I attempted to make this subject, a bench in floodwater, more interesting by composing it precisely within the frame. Order, proportion, harmony, and symmetry in the arts are often considered to be pleasing and interesting. Disorder and disharmony in the composition of a photo can lead to rejection and anxiety in a viewer.

I took a number of photos of this park, and the results were always poor, but dusk made the scene more colorful, and I think, more interesting.

A brightly colored photo is appealing, since color attracts attention and color has long been considered a component of beauty. But some people think that unusually or implausibly colored shots are manipulative, garish, or pandering to baser instincts, or are somewhat lacking in true art. For example, someone told me that they disliked my balloon photo above because it was too ’typical’ of an easy, appealing photo. See the article, The Red Shirt School of Photography, which should not be confused with another kind of Red Shirt.

We don’t need bright color to produce an interesting landscape image. See the article How the Wild West REALLY looked: Gorgeous sepia-tinted pictures show the landscape as it was charted for the very first time. These 19th century images show good subjects, good composition, good camera work, and often show human interest, but these images are all monochrome, and yet they are quite effective.

While adding saturation to an image may be questionable or even controversial, artificially adding sharpness to a digital image is almost always needed to produce a better final image. Similarly, local contrast enhancement is often an improvement. Cameras don’t see as the human eye sees, and we often have to make image corrections. Sharpening can be easily overdone, making a photo look rough; undersharpening, on the other hand, will look less than prime.

This shows the same image, using different resizing algorithms. The first is softer than the second, and I think it is less interesting because of that. Please note that there is a quality of blur than can differ between images, and photographers highly value those lenses known for good blur. However, in the digital age, we also need to take into consideration the varying quality of resizing and sharpening algorithms. A quality high-resolution image, properly resized, will look generally look better than a similar image of the same size taken with a lower resolution camera.

It helps to look at your successful photos — those that you and other people like — and attempt to determine why they may be successful. This image is popular. I think that the quality of the light here, and the color of the foliage, helps strengthen it.

Depending on where you live in the world, seasonal changes may help make landscape photographs more interesting. Here we see the trees leaves changing color and some flowers in the foreground. Normally, overcast skies are inferior for landscapes, but here we have good lighting over most of the scene, and the color of the fall foliage makes the scene more interesting. Because of the soft lighting, I was also able to bring up lots of significant detail in the main subject, the statue, and not lose too much texture in the shadows. I think I was fortunate in that the bronze color of the statue was significantly distinct from its background.

Consider an image taken here in summer under broad daylight — would a uniform mass of dark green tree leaves in the background help or harm it? What about the harsh lighting of midday? Or how about in winter — would bare tree branches add anything positive to the image? Or, was this image taken under fortunate conditions?

I hand-held the camera while taking this image of an island in a river; the scene was illumined by the light of a half-moon obscured by clouds, and underexposed by five stops. Only about two digital bits of usable tonality are left in this image, giving us a severely abstracted representation of the original scene. This might be suitable for exhibit in an avant-garde gallery, since it comes very close to the limits of photography, and is almost a pure exercise in form and shadow. It is not, however, a pretty landscape photo.

Imagine if the Superbowl were to be stripped of all inessential elements such as the flashy advertising and elaborate half-time show, and was only a well-played football game. True football fans would perhaps prefer this kind of less-distracting, more focused kind of a game. Likewise, many in the art world more appreciate a photograph that cuts distractions to a minimum, a photograph that gets to the core of photography and the subject. The general public may beg to differ, for the Superbowl also has a social aspect, and so we usually have a disconnect between the desires of experts and the wider population, in sports and in the arts. For example, if you visit the Grand Canyon with your family, you most certainly ought to photograph your kids in front of the canyon, for the sake of the family album, but don’t expect that to appeal to fine arts professionals.

The English word ‘abstract’ comes from the Latin ‘abstractus,’ meaning “drawn away,” and so that word usually means is a taking away of details. One photograph that is more abstract than the other will have less detail than the one that is less abstract. In my opinion, because of how human perception and memory works, I think that a certain level of abstraction is essential in quality photography. Of course, every photograph draws a lot away from the original subject, but I think that even more abstraction than a typical snapshot is necessary to have a good final image.

Herein lies a paradox. Image quality is usually preferred. Most viewers of two otherwise identical photographs will prefer the one that has higher image quality. But most viewers will also prefer an image that has less inessential detail than another. In one study of thousands of photographic portraits, test subjects, on average, rated images with narrow depth of field higher than those with deep depth of field — that is, they rated the more abstract images much higher than those which were less abstract. High quality is appreciated, but having a more abstract final image is also appreciated.

Here is roughly the same scene as above, but taken with more care. This is certainly more suitable for a popular photo book, but notice how there is more distracting detail, such as the leaves on the right and the logs in the center. I think a superior image would eliminate these details, and zoom in a bit closer to the main channel of the watercourse. I have a number of images of this spot taken at midday, but they are hardly notable.

I thought that this image of a forest path would be interesting, but it turned out disappointing. We have a nice winding path, but the tree trunks and branches have little order and so are confusing.

This visually similar photo of a river gets far more notice. The texture on the leaves is complex, but is more uniform than in the previous photo. This photo is simpler than the previous one. One flaw, however, is the dam near the top of the stream, which breaks the visual flow of the image.

The size of an image, its resolution, and the distance from which the image is viewed is important. Many photographers who intend to show their photos primarily on the Internet will produce images that are significantly simpler than those who sell large, high resolution prints. Significant, eye-catching detail on a large print can be much smaller than what can be seen on a thumbnail image. Very large prints are a trend in high-end fine arts photography, and these huge prints — often yards wide — tend to have an extreme amount of detail. Larger, more detailed images can have a more complex composition, since the viewer will visually subdivide the image into smaller compositions — and the task for the photographer is to make these smaller compositions harmonize with each other.

Final Ideas

- Landscapes are not about you, for they are things in themselves, and so a landscape photo ought to clearly show what is true about the scene you are photographing. A heavily manipulated and composited image may be an interesting exercise in digital art, but it is not a landscape photo. If your intent is to show a mood or feelings, then more artifice is allowable, and necessary — your viewers ought to be given clues that your photo is not a natural landscape.

- Unlike many other forms of photography, landscapes do not suffer gimmicks or mistakes very well. Use good gear and technique, and get out of the way of the scene itself. Composition is likely to be difficult, so take your time in finding a good camera position.

- Landscapes are subtle, and photography tends to flatten out subtleties, which require us to shoot something extraordinary merely to make the image look normal. The final image ought to please, delight, or move your audience; if it does not, then the image is a failure.

See also the article Giving Credit...; thanks to my friend Tina, who has a good photographic eye and often suggests good camera positions, and who is very supportive.

2 comments:

I see my footprints!

I like the picture of the river with the log in it. I think it gives texture to an image that would otherwise be flat and unremarkable. I agree the leaves are distracting, but cropping could handle that. I think the log give it uniquness

I had a thought about the trail photo that was slightly disappointing. You took that standing up right? WIth the camera about 6 feet from the ground? I wonder if it would have been better from the ground....

Post a Comment